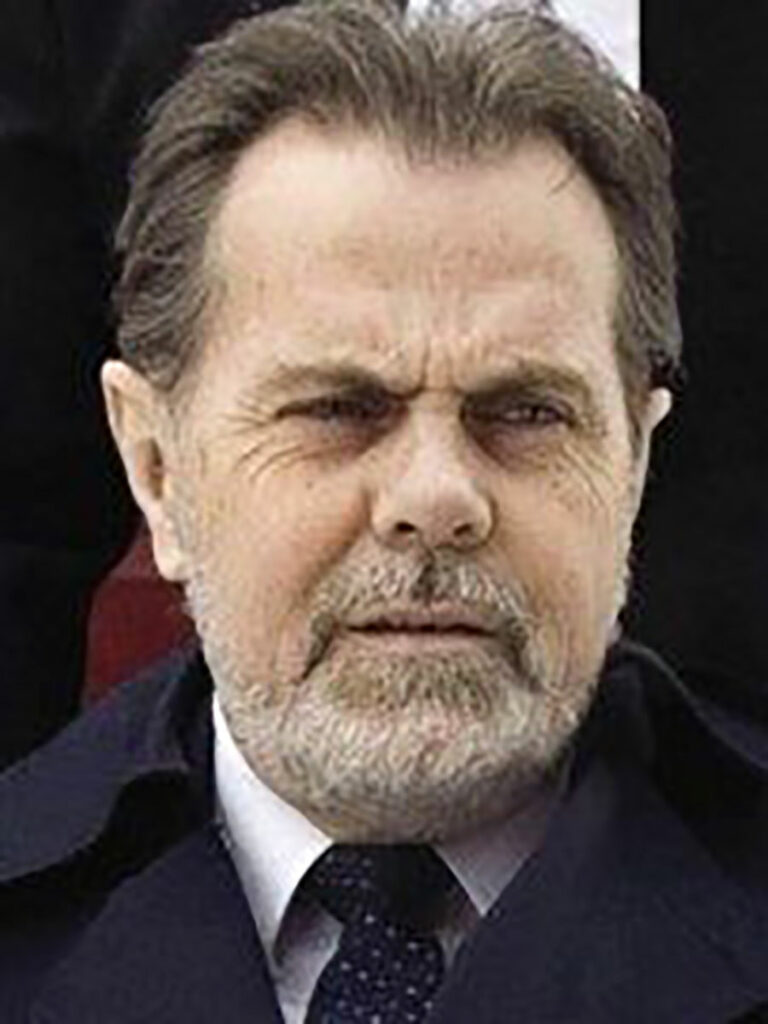

Erin Walsh

Author: Sarah Harland-Logan

Introduction

Erin Walsh was not a saint, but nor was he a killer. He spent over 30 years trying to prove it.[1]

On August 11, 1975, Erin and his friend George Ferguson arrived in Saint John, New Brunswick, hoping to do some business. Specifically, they were planning to sell methamphetamine, which they had bought in Montreal. That night, Erin and George went drinking and met several locals, including Donald MacMillan and David Walton. The next morning, the friends met up with Donald and David again and discussed Erin’s drug-selling plans. They were soon joined by a fifth man, Melvin “CheChe” Peters. All five then drove to nearby Tin Can Beach.[2]

At the beach, Erin took off his shirt and waded into the bay. Looking up, he suddenly noticed that his Cadillac’s trunk was open. Suspicious, he waded back to the beach and checked his shirt pocket for his keys. He discovered that they were missing. Erin had only a few moments to get angry before Donald, David and CheChe attacked him. Erin found himself on the ground, facing the wrong end of a sawed-off shotgun.[3]

Erin’s assailants demanded to know where he kept his methamphetamine and money. He truthfully told them that both were in his car. Erin then made his escape and ran up a nearby embankment, where several men were working on the railroad tracks. Fearing for his life, he asked them to call the police.[4]

Soon after, his friend George caught up to him, and explained that the other men had calmed down and that they had only been “joking”. Erin and George then headed back toward Erin’s car. It turned out that the other three had not been joking at all: they intercepted Erin and George en route to the car, and forced Erin into the front seat at gunpoint.[5]

Donald, David and CheChe then started discussing what they should do with Erin. Donald said that they had to “get rid of him somehow.” CheChe replied that they should simply “blow his head off right here.” Knowing he had nothing to lose, Erin made a desperate grab for the shotgun, and several people then struggled for it. Erin heard a shot but did not know exactly what had happened: he would later recount that he “went into a state of shock temporarily.” That said, he thought that it was Donald who had ended up with the gun.[6]

One thing that was perfectly clear was that CheChe had been shot. The car’s occupants soon heard a police siren. As the Court of Appeal would later phrase it, CheChe then fell out of the car, “got up, staggered to the police cruiser, opened the back door and fell across its seat.” The police promptly arrested all four men who were still in Erin’s car. CheChe was rushed to the hospital, but soon succumbed to the gunshot wound he had taken to the chest.[7]

Later that day – August 12, 1975 – Erin was charged with CheChe’s murder.[8]

Erin’s Trial

At trial, the Crown presented a very different view of what had happened in the minutes leading up to the shooting. The prosecution called Donald and David, who claimed that rather than attacking Erin, they had all just been drinking together. In their version, the only person who was causing problems was Erin himself: they claimed that he had been making racist remarks aimed at CheChe, who was African-Canadian. They also claimed that the shotgun belonged to Erin, and that he had purchased both the gun and its ammunition during his stay in Saint John. Finally, Donald and David testified that once the men had returned to Erin’s car, he had – most implausibly – “reached under the front seat, pulled out the firearm and shot Mr. Peters, who was sitting in the back seat minding his own business.”[9]

Erin tried to explain what had really happened; but he had no evidence except his word, which the jury did not believe. In fact, they were so convinced of his guilt that their deliberations only took an hour, including a break for lunch.[10]

On October 17, 1975, Erin was convicted of the second-degree murder of CheChe Peters. He spent the next 10 years in jail for a crime that he did not commit, followed by additional stints in prison for parole violations. From the beginning, Erin always insisted that he was innocent.[11]

The Emergence of Hidden Evidence

For the next 33 years, Erin fought to clear his name. He first appealed his case to the New Brunswick Court of Appeal, but the court was not persuaded. Undeterred, Erin wrote to every official he could think of, trying to get more information about his case, even when he knew that the parole board would hold these efforts against him.[12]

In 2003 – 28 years after his conviction – Erin wrote to the New Brunswick Provincial Archives, and at long last received a helpful response. The Archives sent him the complete Crown file of his case. What he found there would clear his name.[13]

Erin soon realized that the Crown had kept him in the dark about several serious problems with their case against him. Most crucial of all was the fact that police had overheard Donald and David discussing what had really happened, while waiting after their arrest in the cells. David had asked Donald, “What did you shoot CheChe for?” – to which Donald had replied, “You’re going to help me out, aren’t you, Dave?” The two then started coming up with the story that would draw attention away from Donald and point the finger at Erin instead.[14]

In addition to the record of this conversation – which would have seriously damaged the credibility of both Crown witnesses – the police also had a statement from the owner of the hardware store where Erin had supposedly purchased shotgun shells. The statement made it clear that Donald was the real purchaser. In fact, he bought the shells before Erin had even arrived in Saint John.[15]

Moreover, the Crown file also contained statements from seven Canadian National Railway employees, all of whom agreed that Erin had indeed fled from the beach and asked them for help. Taken together, these three new pieces of evidence made it clear that Donald and David had lied to the jury about the events that led to CheChe’s death.[16]

Finally, the file included a ballistics report showing that both versions of events were consistent with the ballistics evidence. Since Erin had not been provided with this report, he did not have enough information to ask the ballistics expert effective questions and properly support his side of the story. At his own trial, Erin had been flying blind.[17]

A Miscarriage of Justice

In late 2006, Erin, with Innocence Canada’s (formerly AIDWYC) help, filed an application with the Federal Minister of Justice for a review of his conviction (as per s. 696.1 of the Criminal Code). He argued that the extensive new material he had discovered in the Crown file proved that he was innocent.[18]

Sadly, Erin had just been diagnosed with terminal cancer. He was now fighting not only to clear his name but also for his life. As a result, the New Brunswick Court of Appeal made every effort to hear his case promptly, as soon as the Minister of Justice approved Erin’s application in February of 2008. The process was also expedited because the Crown now agreed that Erin had suffered a miscarriage of justice and that his conviction should be quashed.[19]

On March 14, 2008, the New Brunswick Court of Appeal found that no reasonable jury, in possession of all the evidence, could have found Erin guilty of CheChe’s murder. Therefore, the Court quashed Erin’s conviction and entered an acquittal. More than three decades after his wrongful conviction, Erin had finally cleared his name.[20]

Causes of Erin’s Wrongful Conviction

Erin was wrongly convicted because he was never provided with the evidence that he needed to make his case. The Supreme Court made it crystal clear, in its 1991 decision R v Stinchcombe, that this behaviour from the Crown is not acceptable. Rather, the prosecution is required to disclose any and all potentially relevant documents to the defence (except for a few types of privileged materials).[21]

As the Supreme Court held in Stinchcombe, “The right to make full answer and defence is one of the pillars of criminal justice on which we heavily depend to ensure that the innocent are not convicted.” Failing to provide the defence with all the relevant evidence can prevent the accused person from receiving a fair trial, which of course can lead to a wrongful conviction, as it did in Erin’s case.[22]

In its Stinchcombe decision, the Supreme Court also quoted from a much earlier judgment, Boucher v The Queen. In this celebrated 1955 case, the Supreme Court clarified that the prosecutor’s goal is not to win cases, but rather to ensure that justice is done:

It cannot be over-emphasized that the purpose of a criminal prosecution is not to obtain a conviction, it is to lay before a jury what the Crown considers to be credible evidence relevant to what is alleged to be a crime. Counsel have a duty to see that all available legal proof of the facts is presented: it should be done firmly and pressed to its legitimate strength but it must also be done fairly. The role of prosecutor excludes any notion of winning or losing; his function is a matter of public duty that which in civil life there can be none charged with greater personal responsibility. It is to be efficiently performed with an ingrained sense of the dignity, the seriousness and the justness of judicial proceedings.[23]

After all, when an innocent person is wrongly convicted, nobody wins.

Wounds that Innocence Canada Cannot Heal

After Erin’s acquittal, he told reporters that “This is the best day of my life” – “I’ve been working hard towards it for 33 years and finally it’s here.” Now he could say the words, “I’m a free man,” and mean them: “freedom now means something to me. It is not just a word. It is something that I’m going to wear every day of my life like I wore my captivity.” Erin’s description of his newfound freedom makes it clear that until his long-overdue acquittal, a part of him remained behind bars.[24]

Far too soon after fully gaining his freedom, Erin passed away, after a four-year battle with colon cancer. He died at home in Kingston, surrounded by his family, at age 62.[25]

In the words of Innocence Canada lawyer and Director Sean MacDonald, “The fact that a doctor gave him six months to live in August of 2006 and he went on to engage in what would become an epic fight for justice after being diagnosed with terminal cancer speaks for itself.”[26]

[1] See Sean MacDonald, “Erin Walsh Exonerated After 33 Years.” (Spring 2008) Vol. 9 AIDWYC Journal, pp. 3-4 [“Exonerated”]; Chris Morris, The Canadian Press: “Dying Man Acquitted of 1975 Murder Conviction.” March 14, 2008, available at The Star: http://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2008/03/14/dying_man_acquitted_of_1975_murder_conviction.html [“Dying Man Acquitted”].

[2] Walsh v New Brunswick, 2008 NBCA 33 at paras 10, 15, 19, 238 CCC (3d) 289 [Walsh].

[3] Ibid at paras 11, 23-24.

[4] Ibid at paras 25-26.

[5] Ibid at paras 27, 31, 33.

[6] Ibid at paras 33, 35.

[7] Ibid at paras 34, 36.

[8] Ibid at para 2.

[9] Ibid at paras 2, 10, 21, 65, 75; “Exonerated,” supra note 1 at p. 3.

[10] “Exonerated,” supra note 1 at pp 3-4.

[11] Walsh, supra note 1 at paras 3-4; “Dying Man Acquitted,” supra note 1.

[12] Exonerated,” supra note 1 at p. 3; Walsh, supra note 1 at para 3; “Dying Man Acquitted,” supra note 1.

[13] Exonerated,” supra note 1 at p. 4.

[14] Walsh, supra note 1 at paras 38, 80, 89, 94.

[15] Ibid at paras 66-68.

[16] Ibid at para 72.

[17] Ibid at para 76.

[18] Ibid at paras 1, 4.

[19] Ibid at paras 6-7, 45; “Exonerated,” supra note 1 at

[20] Walsh, supra note 1 at paras 91, 99; “Exonerated,” supra note 1 at p. 3.

[21] R v Stinchcombe, [1991] 3 SCR 326, [1991] SCJ No 83.

[22] Ibid at para 11.

[23] Boucher v The Queen, [1955] SCR 16 (Rand J) at pp. 23-24 (emphases added).

[24] “Exonerated,” supra note 1 at p. 3; “Dying Man Acquitted,” supra note 1.

[25] CBC News: “Man Wrongfully Convicted in N.B. Murder Dies.” October 14, 2010: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/man-wrongfully-convicted-in-n-b-murder-dies-1.912058.

[26] Ibid.